Digital Imaging

Enhancing Images and Ethics

Paul R. Montague, CRA FOPS

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences

The Univesity of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

Iowa City, Iowa

Enhancing Digital Images

In ophthalmology, retinal images are used in making a diagnosis, in determining a course of treatment, and in following changes over time. This scientific application requires standardization in the way images are acquired, processed, and presented to ensure reliability of interpretation.

Enhancement of silver photographic images is a matter of routine. Image contrast can be controlled through the choice of developers and printing papers, tone can be altered, and small parts of an image can be made darker or lighter during the printing process.

Digital imaging provides a much more extensive collection of image manipulation possibilities. Since digital images are nothing more than a set of numbers, corrections can be made based on pixel statistics and enhancements can be standardized so that all images are enhanced in exactly the same way.

Before considering image enhancement, it is important to realize that the original image, obtained before any enhancement is performed, contains the most accurate information available. Alterations to that original image are performed to make characteristics of that image more apparent to human observers. Resolution is never increased through the enhancement process, and care must be taken not to enhance an image to the extent that features are identified which did not exist in the original subject.

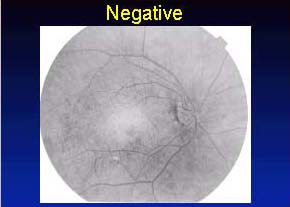

With a film image, the original negative always contains more information than a positive image made from the negative. This loss is due to imperfections in the photographic process. With digital imaging, photographs can be changed at will from negative to positive with no loss of information.

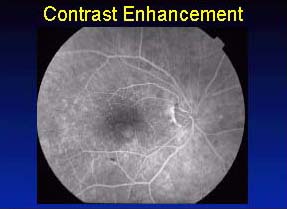

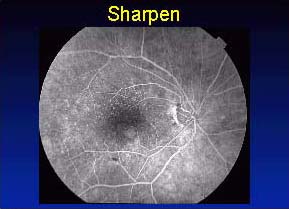

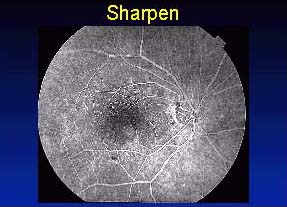

There appears to be reduced contrast in the unaltered image. There are no areas which are pure white or pure black. Of the total available range of 256 gray values, only values between 40 and 160 are present. The contrast can be stretched, moving the 160 values up to 255. The result is an image with higher contrast.

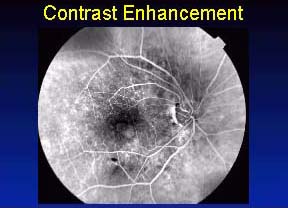

Further enhancement is possible by stretching the low value of 40 down to 0. It is possible to apply this technique to the point where near-white areas in the image become white, and near-black areas become black. At this point, image information is being lost.

A more sophisticated enhancement technique can make the image appear sharper. Let's say a white book lying on a black desk is photographed. If rendered perfectly, the edge of the paper would appear as a line of white pixels next to a line of black pixels. If the image were out of focus, examination of the edge would reveal a smooth transition from white to black several pixels wide.

White on black image.

In-focus and out-of-focus enlargements of one edge.

A computer program can be employed that steepens the transition between dark and light areas in the image. The effect is that edge appears to be sharp in the enhanced photograph. Careful examination revels that the sharp delineation in the original has not been exactly reproduced.

Out-of-focus image after sharpening.

These techniques can be applied to fundus photographs. The observer must realize that the enhanced image will not exactly match one which was precisely in focus at the start.

The amount of sharpening can be varied. A program might offer 6 levels of sharpening, level 1 being minimal and level 6 being maximum. One difficulty with sharpening and edge detection programs is that they can be applied to the extent that they identify and display edges which do not exist in the original image.

Manufacturers of digital fundus cameras are keenly aware of the possibility of over-enhancement. The original image is always stored, without enhancement, so it can be recalled at any time. The enhancement tools which are provided with these instruments are chosen to allow manipulation within conservative limits. It is still important that the observer pay close attention to the enhanced image, comparing it with the original, to confirm that the results are reasonable.

Ethics of Altering Images

The use of digital imaging programs to enhance ophthalmic images has been described in Enhancing Digital Images. Manufacturers of ophthalmic imaging equipment limit computer programs to those which will be safely useful in manipulating medical images.

However, images collected by diagnostic equipment can be exported and altered by a vast collection of commercially available imaging programs which were designed to give the user maximum flexibility in image alteration. This kind of image processing leads to a number of ethical questions surrounding digital imaging.

Assume that a patient is seen at a baseline visit, appropriate drawings and charting are performed, but retinal photographs are not obtained. On follow-up, a highly unusual change occurs. Retinal photography is performed, but the lack of baseline photographs greatly reduces the chances that the case can be used for teaching or publication. Is it possible to make alterations to the follow-up photographs to illustrate the appearance of the retina at baseline?

The original fluorescein angiogram on the left was modified with a digital darkroom program, removing some of the retinal vascular abnormalities. In concept, this is no different than preparing an illustration of the retinal appearance at baseline. But the two images appear so similar that they might both be considered photographic documentation, even if a proper disclaimer were made.

Digital imaging presents the field of ophthalmic photography with a wide variety of powerful tools that can be applied easily to aid in the diagnostic and treatment process, to standardize documentation, and to prepare teaching and publication materials. The application of these tools requires scrutiny and care to preserve the scientific integrity of the images we produce.

|